Introduction

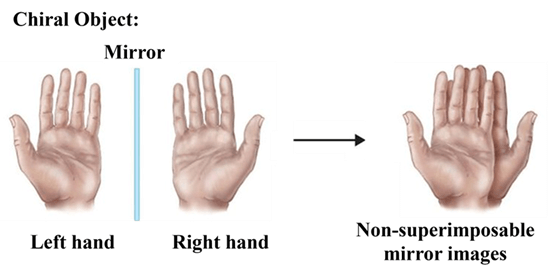

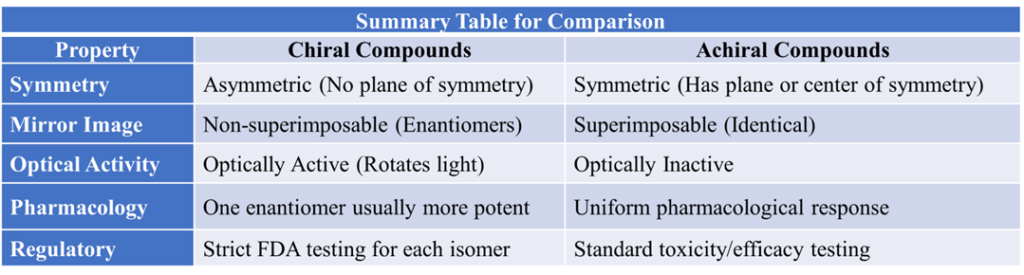

In the world of chemistry, chirality is all about “handedness.” Certain molecules have a specific spatial arrangement that makes them unique from their mirror reflection. The pharmacological profile of a drug is dictated not only by its chemical formula but also by its three-dimensional spatial orientation. In pharmaceutical chemistry, molecules are classified into chiral and achiral based on their symmetry. A chiral molecule is one that cannot be superimposed on its mirror image, a property known as ‘handedness’ that arises from the presence of a stereocenter. Conversely, achiral molecules possess internal planes of symmetry, making them identical to their mirror reflections. For a pharmacy professional, understanding this distinction is critical, as the human body is a highly stereoselective environment where the ‘fit’ between a drug and its chiral receptor determines therapeutic efficacy, metabolic pathways, and potential toxicity.

Chiral Molecules

Definition

A molecule is chiral if it cannot be superimposed on its mirror image. Just like your left and right hands are mirror images of each other but cannot be perfectly overlapped. Think of it like a shoe: a left shoe and a right shoe are reflections, but you can’t wear a left shoe on your right foot and have it fit perfectly.

Key Characteristics:

- Asymmetry: They lack an internal plane of symmetry.

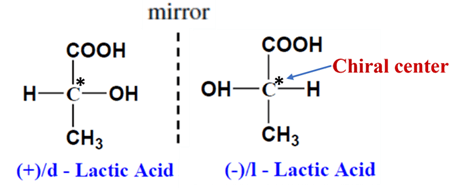

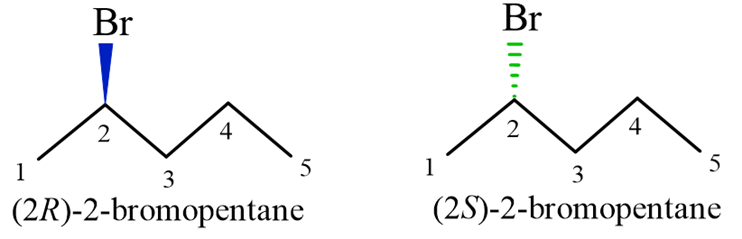

- Chiral Center: Most commonly, they have a carbon atom bonded to four different groups. This is often called a stereocenter. e.g. Lactic acid (2-hydroxypropionic acid)

- Enantiomers: The two non-superimposable mirror images are called enantiomers. They often have identical physical properties (like boiling point) but interact differently with polarized light and other chiral substances (like receptors in your body).

How to Identify a Chiral Molecule

The quickest “cheat code” for identifying chirality in organic chemistry is looking for a chiral center.

The Checklist:

- Find a Carbon atom: Look for “sp3 hybridized” carbons (carbons with four single bonds).

- Check the Neighbors: Look at the four groups attached to that carbon.

- Are they unique? If all four groups are different, you’ve found a chiral center. If even two groups are the same (e.g., two Hydrogen atoms), the molecule is achiral.

- The “Symmetry” Shortcut: If you can draw a line through a molecule and both sides are mirror images of each other (a plane of symmetry), it is achiral, even if it looks complex.

How to Draw Mirror Images (Enantiomers)

When drawing these, we use wedge-and-dash notation to show 3D depth.

- Solid Wedge (

): Points toward you (out of the page).

): Points toward you (out of the page). - Dashed Wedge (

): Points away from you (into the page).

): Points away from you (into the page). - Normal Line (—): In the plane of the paper.

The “Inversion” Technique: You can simply swap two groups on the chiral center. Usually, swapping the wedge and the dash on the same carbon will create the enantiomer.

Achiral Molecules

Definition

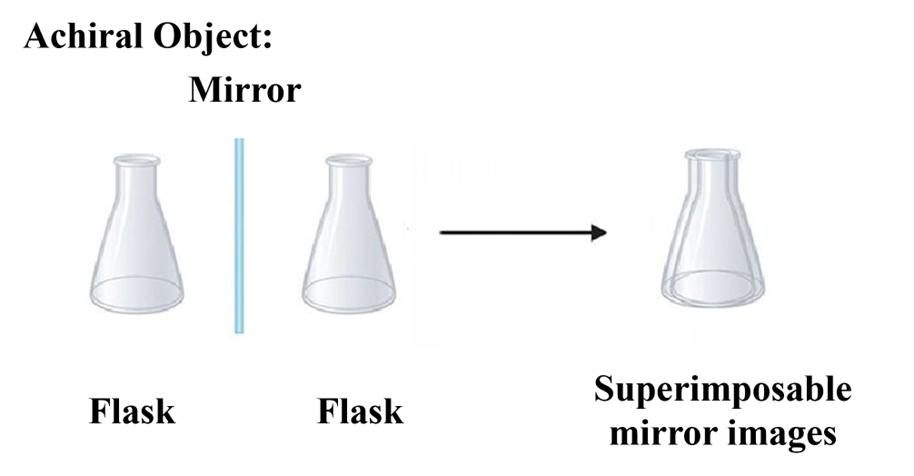

A molecule is achiral if it is superimposable on its mirror image. These are the “flasks” of the molecular world—it doesn’t matter which one you pick up; they are identical. Think of it like a “socks”: it doesn’t matter which one you pick up; they are identical and fit perfectly.

Key Characteristics:

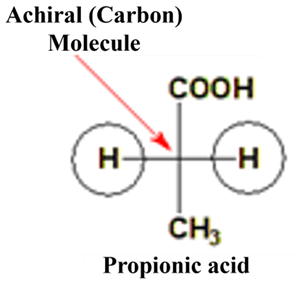

- Symmetry: They possess an internal plane of symmetry or a center of symmetry. If you can slice the molecule in half and both sides are identical, it is achiral.

- Identical Mirror Images: If you rotate the mirror image, it becomes exactly the same as the original.

- Absence of Chiral Centers: Most simple achiral molecules lack a stereocenter (a carbon with four different groups).

- Optical Inactivity: Unlike chiral molecules, achiral molecules do not rotate the plane of polarized light.

Why does this matter?

In pharmaceutical chemistry, chirality isn’t just a technical detail. Because your body’s receptors, enzymes and DNA are also chiral, they can distinguish between two enantiomers. It is often the difference between a life-saving medicine and a dangerous poison. They interact with drugs like a “lock and key.”

One version of a drug might cure a headache, while its mirror image might do nothing at all—or in some famous historical cases, cause harm. The most famous (and tragic) example of chirality in industry is Thalidomide. In the 1950s, it was sold as a mixture of both enantiomers to treat morning sickness. The (R)-enantiomer was a safe sedative. The (S)-enantiomer was a potent teratogen (causing severe birth defects).

Economic and Industrial Impact: “Chiral Switching”

Ease of Synthesis (Lower Production Costs) and Quality Control

Synthesis of achiral drugs is generally cheaper because it doesn’t require expensive chiral catalysts, enzymes, or complex “chiral pool” starting materials. Since there are no enantiomeric impurities to monitor, the analytical validation (using HPLC or Polarimetry) is much simpler.

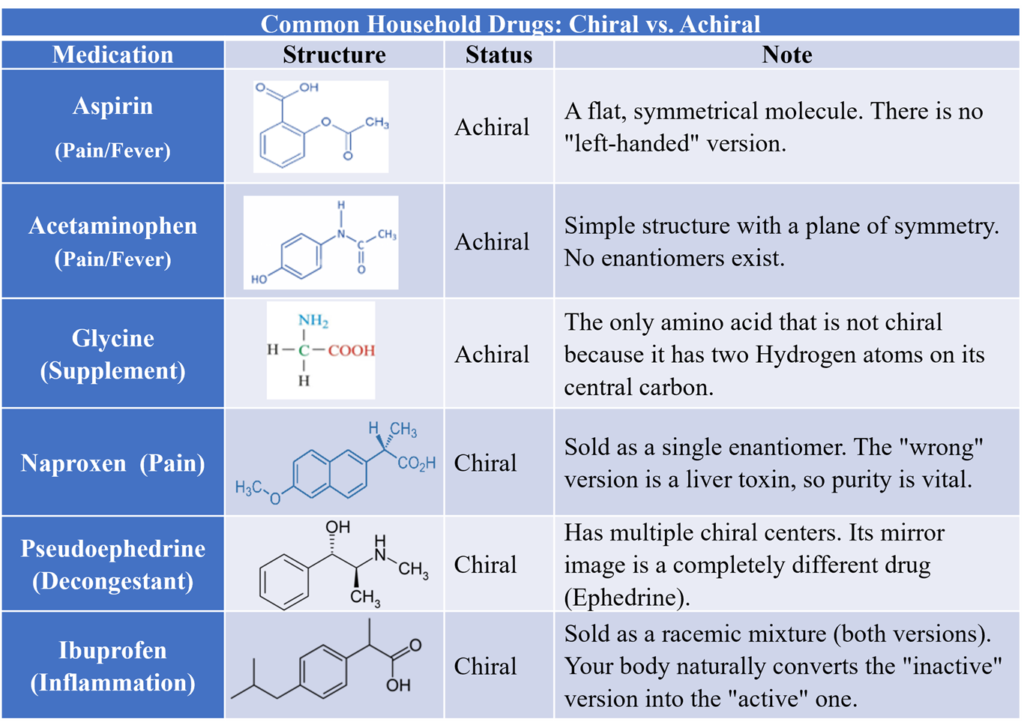

Common Achiral Drugs

Glycine is the only achiral amino acid. Because its side chain is a simple Hydrogen atom (H). Acetaminophen (Paracetamol) is widely used analgesic. Its structure is flat (planar) and symmetrical, making it achiral. Aspirin (Acetylsalicylic acid) is another major achiral drug because it lacks any carbon bonded to four different groups.

Achiral Compounds as Excipients

Solvents such as water, ethanol, and glycerol are achiral and used as vehicles for drug delivery. Preservatives like benzyl alcohol and parabens are achiral. Achiral excipients are often preferred as they are chemically stable and do not undergo racemization (the conversion of one enantiomer to another over time).

Chiral Switching

Modern medicine is moving toward using single-enantiomer chiral drugs. The pharmaceutical industry often uses Chiral Switching, where a company develops a drug as a racemic mixture (50/50 mix of both enantiomers) and later “switches” to a pure single-enantiomer version. Example: the process of developing a single-enantiomer drug from a previously patented racemic mixture (e.g., Omeprazole → Esomeprazole). By removing the inactive “distomer,” we reduce the metabolic burden on the patient’s body. It ensures that patients receive the most powerful and least toxic treatment possible.

Summary Table for Comparison

Common Household Drugs: Chiral vs. Achiral