An error is the difference between the measured value and the “true” or accepted value. Even with the best equipment, some error is always present. In pharmaceutical analysis, errors can significantly impact the safety and efficacy of a drug. While errors can never be zero, they must be within the Official Limits set by the Indian Pharmacopoeia (IP).

Formula: Error = Observed Value – True Value

Sources of Errors (The “Where” and “Why”):

These are the “origins” or reasons why a measurement might deviate from the truth. In a pharmacy lab, errors don’t just happen; they originate from specific points in the analytical process.

Instrumental

Using uncalibrated equipment e.g. balances, leaky burettes, or faulty pH meters. Example: A balance that shows a reading of 0.002g even when empty, or a pH meter that hasn’t been calibrated with a buffer or a volumetric flask that was dried in a hot oven (causing the glass to expand and change its volume permanently).

Methodological

These are inherent in the analytical procedure itself. Example: Using an incorrect indicator in titration or incomplete chemical reactions. In an assay of Magnesium Sulphate, if the reaction with EDTA is not given enough time or the pH is not maintained with a buffer.

Personal (Human)

Arise from the analyst’s lack of care or physical limitations. Example: reading the meniscus wrong, mathematical mistakes, or color blindness leading to the wrong estimation of a titration end-point. Loss of Material during the transfer of powder from a weighing paper to a beaker.

Environmental

External factors like changes in temperature, humidity, and atmospheric pressure or vibrations in the lab. Example: Weighing a hygroscopic (moisture-absorbing) substance on a rainy day with high humidity, which increases the weight artificially. A drug like Aspirin breaking down into Salicylic acid (due to decomposition) because it was weighed in a humid environment.

Reagent Sources

Caused by impurities present in the chemicals or solvents used. Using chemicals that are not “Analytical Reagent” (AR) grade. Example: Using tap water instead of distilled water, which introduces chloride and sulfate ions into your reaction.

Types of Errors (The “Classification”)

Errors are scientifically classified based on their predictability and nature. These are broadly classified into following categories:

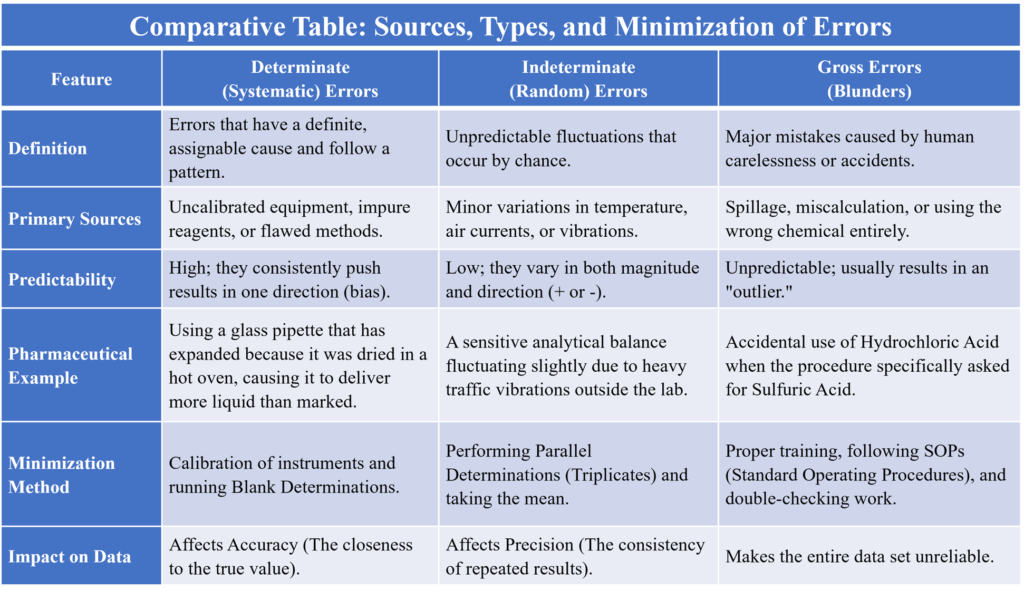

Determinate (Systematic) Errors

These are avoidable and have a measurable value. These have a definite cause and can be identified and corrected. They are usually “one-sided” (results are consistently too high or too low).

Operational/Personal Errors

These depend on the analyst lack of care. Example: In an Acid-Base titration, if you stop the titration when the color is “dark pink” instead of “pale pink,” your result will be consistently higher than the actual value.

Instrumental/Reagent Errors

Example: A pipette calibrated at 20°C, is being used in a room that is 35°C. The glass expands, leading to an incorrect volume of liquid being delivered.

Errors in Methodology

Example: In Gravimetric analysis, if the precipitate (like Barium Sulphate) is not washed properly, it will retain impurities, resulting in a higher “recorded” weight of the product. Using the wrong indicator.

Indeterminate (Random) Errors

These are unavoidable and occur due to unknown variables. They follow a Gaussian Distribution (Bell Curve), meaning small random errors happen more frequently than large ones. Example: Slight variations in temperature while you are performing a 30-minute titration. Even if the same person uses the same pipette to measure 10ml of water five times, they might get: 10.01ml, 9.99ml, 10.00ml, 10.02ml, and 9.98ml. These tiny fluctuations are random errors.

Gross Errors

These are “human blunders” that are so large they require the experiment to be discarded. Example: Accidentally using HCl instead of H2SO4 or recording 25.0 ml as 52.0 ml.

Methods of Minimizing Errors (The “Solutions”)

As a pharmacist, you must ensure results are as accurate as possible using validated techniques:

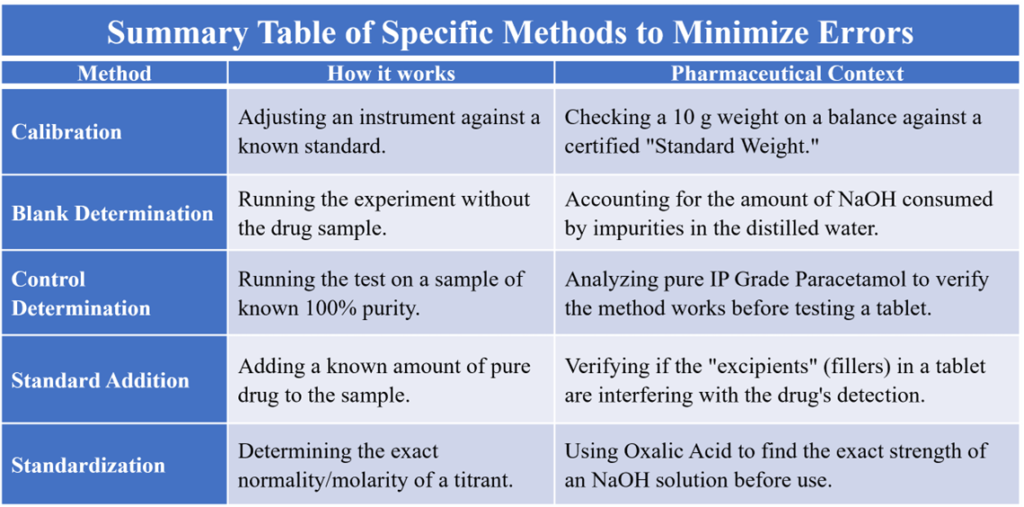

Calibration of Apparatus

Regularly checking and adjusting balances, weights, and volumetric glassware (pipettes, burettes) against standards.

Blank Determination

Performing the entire experiment without the actual drug sample. This tells you how much “error” is coming from the reagents or solvents themselves.

Control Determination

Running the experiment on a “Standard” sample with a known concentration under identical conditions.

Parallel Determinations (Replicate Analysis)

Never rely on one reading. Instead of one titration, perform the same test three times (triplicate) and take the Mean value and Standard Deviation. This helps reduce the impact of random errors.

Standard Addition

Adding a known amount of pure analyte to the sample to check recovery rate. This accounts for “Matrix Effects” (interference from tablet fillers or excipients).

Independent Method of Analysis

Verifying the result using a completely different technique. Example: Determining the concentration of a metal ion using both Titration and UV-Spectrophotometry.

Comparative Table: Sources, Types, and Minimization of Errors

Summary Table of Specific Methods to Minimize Errors