In simple words, rancidity is the chemical decomposition of food that contains fats, oils, and other lipids. It happens when these fats react with oxygen or moisture. It results in unpleasant smell, a stale taste, and a change in color. Beyond the sensory changes, rancidity can reduce the nutritional value of food by destroying essential fatty acids and vitamins (A and E). In some cases, it can produce toxic compounds.

Think of it as the “rusting” of food—just as iron reacts with air to rust, oil reacts with air to turn rancid.

Types of Rancidity

The spoilage of oils generally occurs through two distinct pathways:

Oxidative Rancidity (Auto-oxidation)

This is the most common form, primarily affecting unsaturated fats. It occurs when oxygen from the air reacts with the double bonds of fatty acid chains.

Mechanism: A free-radical chain reaction (Initiation → Propagation → Termination).

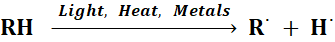

I. Initiation: Under the influence of catalysts like UV light (ℎ𝜈), heat or metal ions (Fe2+, Cu2+), a hydrogen atom is removed from a fatty acid (RH), creating a highly reactive lipid free radical (R˙).

II. Propagation: This is the “chain” part of the reaction. The lipid radical (R˙) reacts with atmospheric oxygen to form a peroxyl radical (ROO˙). This peroxyl radical then attacks another stable fat molecule (R1H), creating a hydroperoxide (ROOH) and a new radical (R1˙) to continue the cycle.

i) R˙ + O2 → ROO˙ ii) ROO˙ + R1H → ROOH + R1˙

III. Termination: The reaction stops when two free radicals collide and form a stable, non-radical compound. This usually happens when the concentration of radicals is high or the substrate (oil) is depleted.

R˙ + R˙ → R-R ; R˙ + ROO˙ → ROOR ;

ROO˙ + ROO˙ → non-radical products + O2

Products: Hydroperoxides, which further break down into volatile aldehydes and ketones (the source of the foul smell).

Example: Old potato chips or nuts left in an open bag.

Hydrolytic Rancidity (lipolysis)

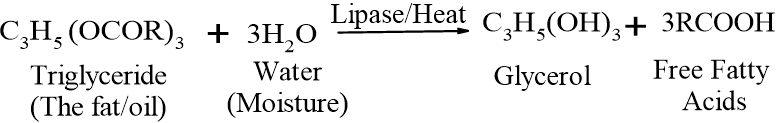

This occurs when water (moisture) breaks the ester bonds of triglycerides into their constituent parts—glycerol and free fatty acids (FFAs). Unlike oxidative rancidity, which requires oxygen, hydrolytic rancidity can occur in airtight environments as long as moisture and a catalyst (like heat or enzymes) are present.

Mechanism: The core of this process is the hydrolysis of the ester bonds that hold a fat molecule together. A triglyceride molecule reacts with three molecules of water to break apart. This is often catalyzed by the enzyme lipase or heat:

How it happens:

- Enzymatic Pathway: Naturally occurring enzymes called lipases (found in plant tissues, milk, or produced by bacteria) act as biological catalysts to speed up the breaking of ester bonds.

- Thermal Pathway: During high-heat processes like deep-frying, the steam from the food provides the water necessary to break the oil’s chemical bonds even without enzymes.

Examples:

i) Stale Potato Chips: If you leave a bag of chips open for a few days, they lose their fresh taste and start to smell like old cardboard. This is because the oil in the chips has reacted with the oxygen in the air.

ii) The “Goaty” Smell of Spoiled Butter: Butter is the most famous victim of hydrolytic rancidity. It contains butyric acid, a short-chain fatty acid. When butter is left in a warm, moist environment, lipases (either from the milk itself or from bacterial contamination) release the butyric acid. Even tiny amounts of free butyric acid produce a powerful, vomit-like or “goaty” odor.

iii) Deep-Frying Oil Degradation: If frying oil is used too many times, it becomes dark, foams up, and smells pungent. When wet foods (like frozen French fries) are fried in hot oil, steam entered into the fat. The combination of high heat (1800C) and water causes the oil to hydrolyze rapidly. As a result, the oil becomes “soapy” and begins to foam excessively. Its smoke point drops meaning it starts to smoke and burn at a much lower temperature than fresh oil.

iv) Raw Nuts and Seeds: Raw seeds contain natural lipases designed to break down fats into energy when the seed sprouts. If nuts are crushed or damaged during storage, these enzymes come into contact with the oil. The nuts develop a bitter, “bitey” taste. This is why many nuts are blanched (heat-treated) to kill the enzymes before packaging.

Factors Accelerating Rancidity

- Temperature: Heat provides the energy needed to initiate the oxidation process.

- Light (UV): Light acts as a powerful catalyst for photo-oxidation, especially in clear bottles.

- Oxygen Exposure: Increased surface area (like in powders or thin films) speeds up air contact.

- Trace Metals: Even tiny amounts of copper or iron from storage tanks can act as pro-oxidants.

- Degree of Unsaturation: Oils high in polyunsaturated fats (like flaxseed or fish oil) spoil much faster than saturated fats (like coconut oil).

Prevention and Control

To extend the shelf life of oils, the industry uses several protective strategies:

- Antioxidants:

* Natural: Vitamin E (tocopherols), Vitamin C (Ascorbyl Palmitate), Rosemary extract.

* Synthetic: BHA (Butylated Hydroxyanisole), BHT (Butylated Hydroxytoluene), TBHQ (Tertiary Butylhydroquinone) etc.

- Modified Atmosphere Packaging (MAP): Flushing packages with inert gases like Nitrogen to displace oxygen (e.g. chips bags are “puffy”). Since nitrogen doesn’t react with fats, it keeps the chips crunchy and fresh for a long time.

- Heat Treatment: Pasteurizing milk or blanching nuts “denatures” (deactivates) the lipase enzymes.

- Minimize Reheating: Repeatedly heating oil, especially at high temperatures for frying, breaks down its structure and accelerates oxidation.

- Opaque Packaging: Using dark glass or metal tins to block UV light.

- Chelating Agents: Substances like Citric Acid are added to “trap” trace metal ions (like iron or copper) so they cannot catalyze the rancidity reaction.

- Temperature: Storing fats in the refrigerator and dark environments to slow down chemical reaction rates.

Storing oils and fats at home (H.A.L.T.)

To prevent oils and fats from going rancid at home, a simple set of guidelines can be followed based on the acronym H.A.L.T. (Heat, Air, Light, and Time).

| Factor | Why it matters | Practical Home Tip |

| H – Heat | Heat provides energy that speeds up the chemical breakdown of fats. | Never store oil above or next to the stove. Store in cool place (15°C and 21°C) or a low cupboard, away from the oven. |

| A – Air | Oxygen is the primary cause of “oxidative” rancidity. | Keep containers tightly sealed. For bulk oils, transfer a small amount to a “daily use” bottle and keep the main container sealed. |

| L – Light | UV rays from sunlight or even bright kitchen lights act as a catalyst for spoilage. | Store oils in dark glass (amber/green) or metal tins. If oil is in a clear plastic bottle, keep it inside a dark cupboard. |

| T – Time | Unlike wine, oil does not get better with age. It starts degrading the moment it’s pressed. | Use within 2–3 months. Check the “Best Before” date and try to use opened bottles within 60 days. |

Comparison Table: Oxidative vs. Hydrolytic

| Feature | Oxidative Rancidity | Hydrolytic Rancidity |

| Primary Cause | Oxygen (O2) | Water (H2O) / Moisture |

| Susceptible Fats | Unsaturated fats (liquid oils) | Saturated & Unsaturated fats |

| Key Catalysts | Light, Heat, Metal ions (Fe, Cu) | Lipase enzymes, High heat |

| End Products | Aldehydes, Ketones, Peroxides | Free Fatty Acids, Glycerol |

| Sensory Change | “Stale” or “Cardboard” smell | “Soapy” or “Pungent” taste |